It has long been argued (accurately) that unlike China and France, India has no historical restaurant tradition. Almost everything we associate with Indian restaurant food today came after Independence and Partition: tandoori chicken, the masala dosa, the Udupi-type restaurant, the Punjabi (Kwality-Gaylords) kind of restaurant, butter chicken, Moti Mahal, the all-India cult of biryani, Indian-Chinese food, etc.

There is only one kind of food (apart from home food) that predates all of these most recent inventions. And that is street food.

It is no surprise then that almost anything of consequence that has happened to Indian food in this century has owed its inspiration to the flavours of the street.

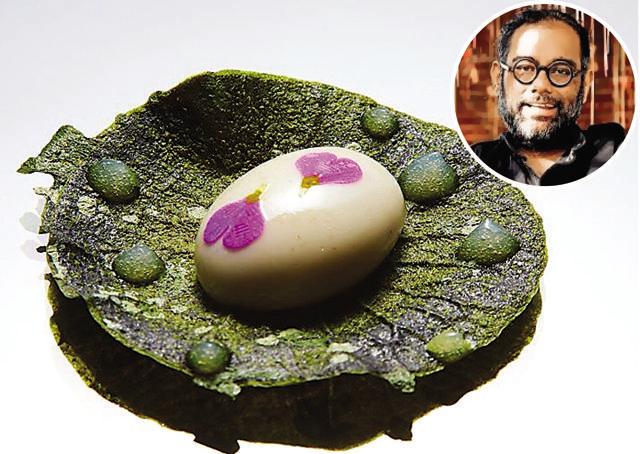

The most significant and influential dish of modern Indian cuisine was invented only a decade ago: Gaggan Anand’s Yoghurt Explosion. It was a great Indian dish because it merged the Indian fascination with dahi with the genius of young Indian chefs. Anand took a technique invented by Albert Adrià (of El Bulli), which would not normally work with a milk product, adapted it so that the calcium content of the yoghurt was not a problem. And then he made it taste of the flavours of the Indian street. (When it explodes in your mouth, you taste papri chaat.)

As Gaggan was experimenting with street flavours (and later with the constituents of mithai: savoury ghewar and jalebi batter), Manish Mehrotra was creating a new kind of Indian cuisine, also drawing from the flavours of the street, at Indian Accent in Delhi.

The two men re-invented Indian food, threw away the old Mughlai template and stopped trying to recreate home food. They took roadside flavours and created food that was not solemn or pretentious. It was just fun.

To be fair, chefs abroad had tried to experiment with street flavours before. Suvir Saran in New York and Vineet Bhatia were ahead of the game but they ran formal, very successful Michelin-starred restaurants so the fun-element was restricted to a few courses.

Gaggan and Manish, who faced none of these constraints, rewrote the book when it came to Indian food. Everything of note that has opened since then has been influenced by their work. When Masala Library (with a kitchen run by two former Indian Accent chefs) opened, the Yoghurt Explosion was on its first menu.

The third member of this trinity was the late Floyd Cardoz. Both The Bombay Canteen and especially the excellent O Pedro, which he opened in Mumbai, played on the same ideas: unusual flavours from the streets and a sense of joy and fun in the food. At The Bombay Canteen, you will find dishes from the streets of Indore. At O Pedro, the flavours of the Goan street explode in a mighty trumpet blast.

I have been waiting for more restaurants to follow this path. There is Comorin in Gurgaon, which I call Manish-Mehrotra-does-Bombay-Canteen except that the food is far better than The Bombay Canteen because Manish is a far better chef than anyone in Mumbai.

And now, there is the Bhawan delivery service in Delhi. And hopefully once life returns to normal, there will be a full-fledged Bhawan restaurant too. (The plans are ready but there was a dispute over the site, and then the lockdown intervened.)

Bhawan is the third major venture from Rahul Dua who made his reputation with Café Lota at the Crafts Museum in Delhi. A former Taj manager (of Souk at the Mumbai Taj), Dua is a self-taught chef. He linked up with former journalist Kainaz Contractor (also a self-taught chef though she was briefly part of the Taj management programme), to open Rustam’s, serving Parsi food.

Though Dua’s background is fine dining (he was the sommelier at Verre, the restaurant Gordon Ramsay used to run in Dubai), he longed to do something simpler on his own and when Café Lota won rave reviews, he decided to try regional food, which is how Rustam’s was born. (Modestly he refers to Café Lota as a “poor man’s Indian Accent”, which at least, tells us what his reference points are.)

Next Dua, and Contractor toured India trying to find the best street food dishes. They came back and created Bhawan, with a massive menu that included the usual stuff, done in the Classical manner (Dahi Bhalla, Sev Puri, etc.) as well as local favourites like Benaras’s Tamatar Chaat, Mumbai’s Ragda Pattice, Himachal’s Chilli Chukh Samosas, Indore’s Bhutte Ka Kees and a Chandni Chowk bowl of chhole, saag and rice.

They played around with some of the dishes (but only, a little) and also created their own street foods. One of their kachoris has bacon and cheddar cheese. They took Goan chorizo and put it inside a bread pakora. They made Gondhoraj lemon pani for their puchkas and they made a killer chaat from karelas.

It is an unusual concept because it is not a modern take on the Haldiram-style halwai: much of the food is non-vegetarian as street food can be all over India. It shares some dishes with The Bombay Canteen (which made bhutte ka kees famous outside of Indore) and there is a conscious tribute to Swati, which is most people’s first port of call in Mumbai for clean street food.

I am sure that Dua and Contractor’s example will be followed by others. I know that during the lockdown I have hardly ever spoken to people who miss say, murg mussalam or paneer pasanda. What people enjoy (and therefore long for ) most are the flavours of India’s streets.

I am a little surprised that India’s hotel chains have not picked up on this – Gaggan, Manish, Contractor and Dua all have Taj backgrounds. But I think that the standalone sector has made it clear that this is the next big wave; not regional, not home food and not molecular.

It is the simple, satisfying taste of the Indian street that we crave.

From HT Brunch, September 21, 2020