Every year, the National Association of Street Vendors of India (NASVI) organises a street food festival in Delhi. And I end up spending at least a couple of days there. This year, the FSSAI got involved and its energetic CEO Pawan Agarwal made it an Eat Right Mela focussing on how street food could be clean and hygienic, and how the vendors could be organised into food hubs in each city, given new carts, and access to clean water. All this will help increase their incomes.

As I do every year, this is my annual street food report.

The waves: The first wave of chaat was North Indian and centred around Delhi and UP. The Dilliwallas didn’t travel much but the UP guys spread out all over India; so too did chaat wallahs from Bihar.

If you look at the famous chaat of Kolkata, you will be surprised to note that the dishes have little to do with Bengali cuisine. In Mumbai, not only did the chaat wallahs of Chowpatty all come from UP, but they were actually called bhaiyas to denote their regional identity.

Of course, the greatness of Indian cuisine lies in the ability of dishes to adapt themselves to local tastes. The puchka of Kolkata is very different from the batasha of say, Lucknow. The pani puri of Mumbai is only a cousin of the golgappa or the puchka. And the greatest Indian chaat invention is bhelpuri, created by the Gujaratis of Mumbai following the lead of the UP chaat wallas.

There was a second channa-based wave, using Delhi/Punjabi dishes like channa bhatura and that wave persists though the flavours vary from region to region. (Amritsar is still the best.) There is no consensus over the rise of aloo-tikki as a chaat dish. (It is still not that big a deal in say, Mumbai.) One theory is that it wasn’t street vendors but halwais who made it so popular.

Since then, the street food scene has branched out in many directions. At the street food festival I saw evidence of all the waves that had gone before. But the one trend that becomes more and more noticeable every year, is the rise of Western, packaged or store-bought ingredients.

Western influence: The first major change in the indigenous street-food tradition was the use of bread (always shop-bought) in such dishes as pav-bhaji and pav-keema. Then, bakery-made hamburger-style buns became essential ingredients of such dishes as the dabeli and the vada-pav.

But, starting with the Bombay sandwich, street food vendors are now relying increasingly on sliced white bread. If it isn’t the bread pakora, then it is some other dish made with Britannia or Modern bread.

Almost as ubiquitous is Amul butter. Pav-bhaji was the first street dish to rely on Amul and now vendors are forsaking desi ghee for tonnes and tonnes of butter.

Also, part of the current street food boom is processed cheese. I have no idea how this started but innumerable dishes now rely on grated cheese: from roadside omelettes to even masala dosas.

Where did the bread-butter-cheese trio come from? How did this trio inveigle itself into an indigenous street food tradition?

I have no idea.

But it is certainly not to my taste.

The bread is usually disgusting and the processed cheese destroys such dishes as the dosa.

Chinese street food: It is a truth universally acknowledged that ‘Chinese’ food in India is now almost as popular (if not more popular) than Punjabi restaurant food. Butter Chicken is nearly passé. Chicken Manchurian rules all over India.

I have written extensively about why umami flavours (which we call “Chinese”) have done so well in India in recent decades so I won’t bore you with all that again.

But so much of what was available at the street food fair was called ‘Chinese’ that I began to wonder why the Chinese needed to attack us in 1962. Noodles and soya sauce have invaded us so successfully that no military action seems to have been required.

The saving grace is that the Chinese are baffled by what we call ‘Chinese’ so may be we have won after all; by colonising and bastardising their cuisine.

At this year’s street food festival, Maggi noodles were more important than golgappa puris or bhaturas. There were dosas with noodles, omelettes with noodles, and even a truly revolting ‘Chinese’ dabeli with Maggi noodles.

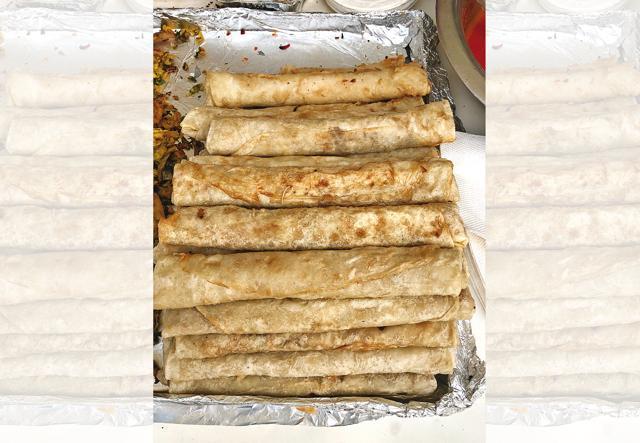

Everywhere I went, there was something ‘Chinese’. One guy sold ‘spring rolls’. Others used the momo for sport. I have just about gotten used to tandoori momos. But the festival had a vendor who served Afghani momos, Achari Momos, Butter Malai Momos and even Bombay Chilli Momos. His main stall is in Karol Bagh in Delhi so I could understand why he made paneer momos, but my head spun when I heard of all the variations he had come up on the basic theme. (As far as I could tell, they were the same momos but he poured different sauces on them.) Other vendors submitted momos to further indignities.

Local foods: The new-style (‘Chinese’ etc.) street food came generally from big urban centres (though the Chinese dabeli comes from Gujarat) but if you went to stalls run by vendors from smaller towns, the original flavours were preserved.

And even many big city chaat wallahs, made the real thing. Dalchand, the Delhi tikki wallah who was featured on Netflix, ran a large stall where he made wonderful aloo chaat and superlative tikkis stuffed with dry dal. He did not use butter and the aroma of desi ghee permeated his wonderful food.

We don’t know much about Orissa street food in Delhi and Mumbai but guided by my friend, the food writer Amit Patnaik, I picked my way through the Oriya section at the festival. All of it was great but I was particularly taken with the Dahi Vada Aloo Dum from Cuttack, which mixed hot and cold, and fiery and soothing to great effect.

I was thrilled to see a guy selling Old Delhi’s famous Daulat Ki Chaat, a dish made world famous in its modern avatar by Manish Mehrotra at Indian Accent. It is roughly the same as UP’s nimish, malai makkhan and malaiyo (though this is a subject of some debate) and can only be made in the winter. It is hard to get outside of Old Delhi so naturally, I had two portions !

I always get stoned for saying this but when you see chaat from all over India side by side, it is clear that Delhi has the worst chaat and that UP has the best (though individual category winners would be Kolkata for puchkas and Mumbai for bhelpuri). There is competition within UP’s towns and cities for the chaat championship but the clear winner at this Festival was Banaras.

The Banaras stalls made an outstanding tomato chaat, excellent batashas (golgappas) and delicate aloo tikkis. Another stall from Banaras made amazing jalebas in front of your eyes. I always thought that a jaleba was no more than a more muscular jalebi, but the man who made it explained the real difference: a jalebi is made from wheat, while a jaleba is made from besan.

Conclusions: Of all of India’s food magicians, the street food guys are the ones I feel worst about. They barely eke out a living, get pushed around by the cops and the authorities and still produce outstanding food.

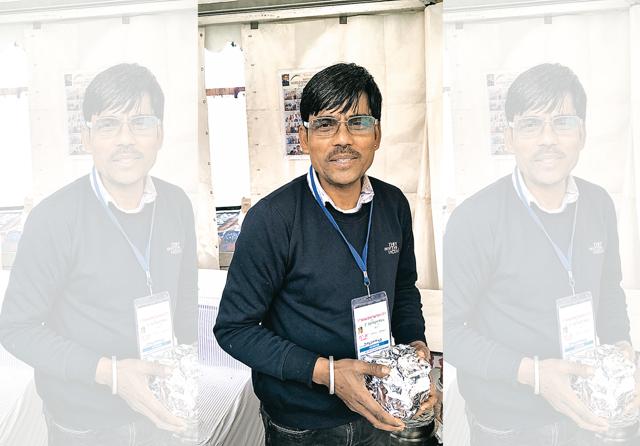

We had organised a competition to find the best street food guys in India. The judges were three great chefs: Vikramjeet Roy, Manish Mehtrotra and Ritu Dalmia.

Banaras won the overall prize as expected but what struck me was how readily the great chefs were willing to learn. Manish fell in love with a litti-chicken dish, which he said he had never come across before and now plans to add it to the Comorin menu.

Ritu Dalmia knew all the trade secrets. (Dalchand’s tikki kept its shape because he used a little arrowroot flour, apparently.) But she took notes and sent her chefs the next day to see how the dishes were made. Manish sent the entire Indian Accent team to the festival too.

For me the most moving part was seeing the hawkers come up on stage to receive their awards. I am so tired of the numerous fancy food awards where the same people come up each year to get bogus awards and then send back advertising to say thank you.

These were possibly the first awards for street food guys from all over India and many were tearful when they picked up their awards. They had never imagined that they would ever hear their names called out and be applauded on stage.

My friend, Sangeeta Singh, organises this festival each year with great effort and though I reckon the event had 36,000 visitors this year over five days, that’s not enough.

You should all go.

Next year, I will write about it in advance and give fair warning.

From HT Brunch, January 12, 2020