As you probably know, one of the triggers for the great revolt of 1857 (or the First War of Independence or the Mutiny, depending on your perspective) was a story that spread across India. According to those who claimed to be in the know, the British army had coated cartridges with animal fat. Soldiers had to bite off the covering of the cartridges to use them. This meant that they ended up eating bits of the animal fat.

But, or so went the story, the fat came from cows and pigs. So soldiers were now required to consume beef fat and pork fat. This offended both Hindus and Muslims and led to revolts in army units.

The British said that no pig or cow fat was used and that the story was just a rumour. But when it comes to the politicisation of food, facts often count for less than perceptions. (And it is entirely possible that the Brits were lying, anyway!) Much of today’s so-called food history tends to be only about perception. Truth seems to matter less and less.

In fact, I am beginning to believe that, at no point since 1857, has food been as politicised as it is today. The renewed furore about beef eating is mostly political. The battle between khichri and biryani is really not about rice dishes at all. It is about so-called Hindu foods and Muslim foods. And the debate is prolonged only for political reasons.

In the popular imagination, a certain caricature of Indian food habits persists. According to this version, good Hindus were always vegetarians. Meat eating was a great sin. Beef eating was an even greater sin. Then, along came the Mughals. They promoted meat eating. They took their biryanis all over India and contaminated the pure vegetarian Indian tradition.

By prosecuting those who eat beef and by honouring vegetarianism, we are told, our country is going back to ancient Indian traditions. We are restoring this great Hindu nation to a time when gods walked the earth and peace ruled the land.

The problem with this caricature is that almost every single fact in it is wrong.

First of all, India was never a vegetarian country. Whether you went North or South in ancient India, the kings usually ate meat. (So did the gods in our epics.) Ancient Indian rulers did not just eat meat or chicken. They ate tortoises, deer, peacocks and other birds and animals.

Even during the Indus Valley Civilisation, one of the world’s oldest urban civilisations dating back to 3,000 years before the birth of Jesus Christ, animals were raised and slaughtered for food. During the Vedic period, non-vegetarianism was common. Even Ayurveda, which we regard now as a purely Hindu vegetarian phenomenon, advocated remedies based on meat.

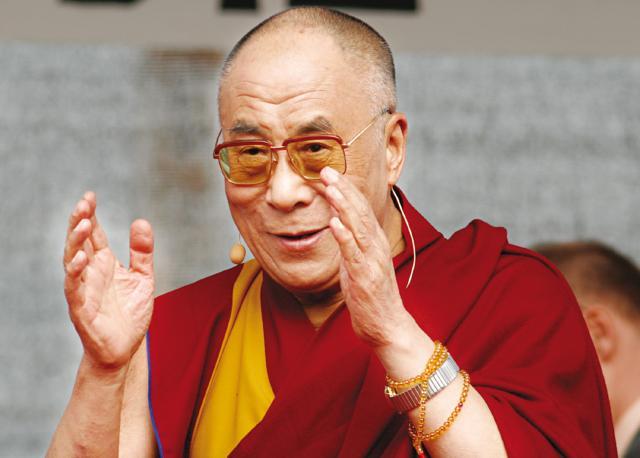

The popularity of vegetarianism came from the Jain, rather than Hindu, tradition. Even the Buddha (who came after Mahavir and the founding of Jainism) did not insist on vegetarianism. (Indians are always shocked to discover that the Dalai Lama eats meat; he ate beef till his doctors told him to go easy on red meat.) Ancient texts such as The Arthashastra contain many references to meat eating.

So, the view that ancient Hindus were all vegetarians is a myth.

What about the Mughals, the subject of much demonisation these days? Well, almost everything that you will read on many popular Internet sites about the Mughals is wrong.

First of all, they did not call themselves the Mughals. That name was given to them centuries later by British historians on the grounds that Babur’s mother may have descended from Genghis Khan. Babur himself would have been horrified to have been called a Mongol or a Mughal.

Secondly, the Mughals did not arrive in India, defeat valiant Hindu kings and then establish a beef-eating, tyrannical dynasty. There had been Muslim rulers in India for centuries. Babur defeated the Delhi Sultanate, a Muslim kingdom and not some perfect embodiment of Ram Rajya.

Thirdly, the Mughals did not turn a peace-loving, grass-grazing, meat-abjuring populace into non-vegetarians. Not only were the Muslim kings before the arrival of the Mughals non-vegetarians, but so were many Hindus.

If anything, the Mughals were actually less keen on meat than many Hindu kings had been. Many Mughal Kings and nobles would give up meat before battles. And the Emperor Akbar developed such a distaste for meat that he became virtually vegetarian in later life. Keeping in mind medieval (but not necessarily ancient) Hindu sensitivities about the cow, he actually banned cow slaughter. He drank only Ganga jal.

Many of these practices were continued by his son Jahangir and his grandson Shah Jahan, both of whom were vegetarian on certain days of the week and continued to impose Akbar’s ban on cow slaughter. (They also drank Ganga jal.)

So yes, the Mughals were non-vegetarians. But then so were many Hindus. And the so-called Mughlai cuisine served in restaurants today does the Mughals a great injustice. Most of the recipes and many of the dishes have nothing to do with the Mughal court.

Which brings us to the whole khichri versus biryani debate. In today’s crude popular parlance, khichri is truly Hindu whereas biryani is some Middle-Eastern dish brought to India by the Mughals.

This is nonsense.

Khichri is Indian but it is not, and never was, purely Hindu. Indians of all religions ate it (Buddhists, Jains and even Muslims). Nor was there only one type of khichri.

In medieval India, any dish that combined grain and lentils came to be called khichri. So there were hundreds of variations.

Let’s take the example of one variation that delighted the Emperor Humayun and the Shah of Persia. One of Persia’s great claims to fame is that it says it invented an early version of the pulao and sent it around the world. It became pilaf in Turkey, paella in Spain and risotto in Italy. But even the Persians will concede that they borrowed one great rice dish from India.

When Humayun lost his throne, he spent 15 years in exile. He spent much of that period in Persia seeking the help of the Shah. During this period, his cooks taught the Shah’s local cooks how to make khichri. This variation used peas and delighted the Shah.

When Humayun reclaimed his throne, this North Indian variation of khichri became a staple of the Mughal court until Jahangir (Humayun’s grandson) found a new kind of khichri while travelling through Gujarat. This khichri was made from millets not rice and it soon became the Emperor’s favourite dish (though the court cooks used more ghee than the Gujarati original). And it was cooked in the palace kitchen nearly every day.

Why was khichri so popular all over India? Not because of our devotion to vegetarian cuisine. It was a one pot meal that used dal (one of the defining characteristics of Indian cuisine through the ages) and any local grain that was available (not just rice). People ate it mainly because it was cheap and easy to cook. During wars, when soldiers would cook their own food, there would often be hundreds of fires lit before a battle as each solider made his own khichri.

Most khichris were vegetarian because even non-vegetarian Indians found meat too expensive. (This was as true of the rest of the world, even England under say, Henry VIII, where the nobles consumed all kinds of animals while the peasantry could not afford much meat.)

Which takes us to biryani. Did it descend from the pulao? Probably, but it had to be wetter, more heavily spiced, was usually ‘assembled’ (the meat and rice were first cooked separately in most biryanis, whereas everything was cooked together in a pulao) and it was a main dish, whereas a pulao was a side dish.

Opinions vary on when it was invented (one popular version gives the credit to Akbar’s cooks; others say it was created a century before) but there is no doubt that it is an entirely Indian dish.

So don’t believe all the currently popular lies about pure vegetarians and evil beef-eating invaders. There is no all-Hindu khichri nor any invader biryani. The history of Indian food is too complex for simple stereotypes. And our cuisine is too great for its history to be twisted to suit the needs of today’s political debates.

Politicians will come and go. But India’s many wonderful cuisines will outlast them all.

From HT Brunch, January 20, 2019