There has been a lot of agitation of late on social media (and in the mainstream press) about the prices charged by five-star hotels. Some people have even suggested that the government should intervene and cap prices.

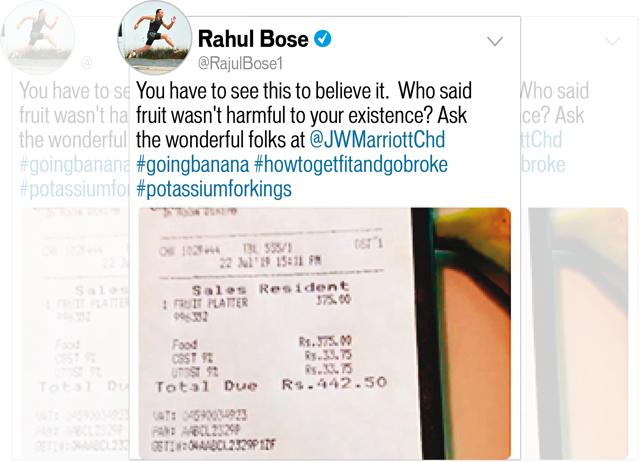

The provocation for this latest uproar has been a series of reports about the price of bananas or the price of boiled eggs at hotels. Aren’t these rates outrageous, people have asked.

Well, frankly, there is only one answer possible: yes, they are.

And is the response offered by these hotels (off-the-record, of course) that if we don’t like their prices we can go elsewhere, adequate?

No. It isn’t.

But things are not as clear-cut and easy as they seem. The first thing you need to recognise is that hotel pricing is becoming a complicated business, highly dependent on systems and computers. Staff have no discretion at many hotels. (Exceptions: the Oberoi and ITC chains.) Most foreign hotel companies rely on systems and give staff almost no leeway.

In the old days, if you wanted a couple of bananas and were a hotel guest, chances are that an (Indian-run) hotel would give them to you for nothing. At the newly-opened ITC Royal Bengal, for instance, there are baskets of fruit lying all around in the corridors. Guests are expected to take as much as they want.

In fully systems-driven chains, however, what happens is this: if a guest asks for a couple of bananas when he is outside his room, the staff member he deals with has to key the order into the computer system. The system will not offer a ‘two banana’ option. Instead, the staff member will have to key in ‘fruit platter’, the only item on the menu that includes bananas.

Obviously, the cost of a full platter is much more than the cost of two bananas. In a good hotel, the staff member should make this clear to the guest. I am not sure if this is actually what happened during the incident in question. But that is probably why the bill was so high. They charged for a full fruit platter.

Silly? Yes. Avoidable? I don’t know. These are the systems on the basis of which hotels now operate.

As for the ₹1,700 for two portions of boiled eggs, that is due to a similar problem. Most hotels will give you, on their breakfast menus, a choice of eggs, all at one price. So whether you order your eggs fried, boiled, in an omelette etc., the price will not vary. The server/order-taker will just key in ‘one portion of eggs’ into the system.

It is intriguing that while people have been so agitated about the price of ₹850 for a portion of boiled eggs, they have not minded so much when the same bill includes exactly the same rate for say, an omelette.

Somehow we find it easier to accept the idea that a five-star hotel can charge ₹850 for an omelette. We just feel annoyed that a boiled egg, a dish that requires little in the way of skill, should cost so much.

In some ways, it is the fruit platter problem all over again.

If you charge only one price for all fruit, then it will seem ridiculous when you charge so much for say, a banana or an apple on its own. If you charge only one price for eggs, then people may not recoil that much at paying for an omelette but they will be horrified to be charged so much for a boiled egg.

Is there a way out? The obvious answer is to offer more options at different price points on the menu. But hotels say that this gets too complicated. Is every room service menu going to have different prices for each fruit? For each egg dish?

A second option is discretion. Empower your staff. If a hotel guest is in the gym and wants two bananas after his workout, give them to him for free. It hardly costs the hotel anything and it makes the guest happy.

If the server doesn’t have the authority to serve a free banana, then he can just ask his superior. But foreign chains (and many Indian ones too) value systems over discretion arguing, reasonably enough I guess, that too much discretion can lead to abuse.

But are five-star hotel prices too high even without these systems-led complications?

There is no easy answer. Hotel pricing is based on demand and supply. You charge – within limits – what you think the market can bear. Obviously, at some stage, other concerns will stop you from going too far. The Maurya could double the prices at Bukhara and the restaurant would still be full. But some sensible person there has worked out the difference between ‘obscene’ and merely expensive.

What most of us don’t realise is that there is a formula to food pricing in hotels. In the old days, the cost of food ingredients was supposed to be one-third of the price the guest was charged. The other two-thirds went on rent, plates, furniture, salaries, electricity, air-conditioning, profit, etc.

This sounds fair enough but most restaurants find it difficult to make a profit on this basis. So food costs are usually lower than a third. Most restaurateurs (even those outside of hotels) will plan for 25 per cent. So the cost of a dish on the menu is four times what the ingredients cost.

Not everyone pulls this off. At many top five-star establishments, food costs can go up to 40 per cent if the chef insists on sourcing the best ingredients from abroad. That, for instance, is why Japanese restaurants find it so hard to survive in India. The cost of imported fish (in rupee terms) keeps shooting up and prices can’t really be increased by the same proportion.

If you look carefully at the menus of most so-called Japanese restaurants in India, you will find that the fish component is steadily decreasing or that cheap, nasty fish is being used. Of course, even then, you can make a profit if you get the right volumes. In Mumbai, Town Hall has the same ingredients and much better food than Wasabi at a much lower price. But that’s because Town Hall can feed hundreds while Wasabi only serves a small number of guests every day. (The Delhi Wasabi, which was actually far better than Mumbai, shut, at least partly because of its high food cost structure.)

But even within the food cost paradigm, restaurants will play tricks on customers. Ever since Bukhara got away with charging high prices for dal, gobi and paneer, other restaurants have followed its lead. The general rule for the pricing of meat dishes is about 25 to 30 per cent food cost. For vegetarian items it is under 10 per cent. Prices on the menu are roughly comparable between vegetarian and non-vegetarian dishes. So vegetarian guests are made to subsidise non-vegetarians. Remember that the next time you are in the mood for some overpriced paneer.

Breakfast and room service can also be minefields. Hotels hate serving breakfast in the rooms. They even hate à la carte breakfast orders. In their ideal world, everyone would just come to the buffet and not bother the kitchen.

There are many reasons for this. One: chefs don’t like having to worry too much about breakfast cuisines. At famous hotels abroad, the dinner may be cooked by a Michelin-starred genius. But the breakfast will be made by the dishwasher.

Two: in many cases (if not most), breakfast is included in the room rate, so guests prefer eating at the buffet rather than spending money on room service breakfast or à la carte items. Hotels take the line that if you have opted not to take a combined rate and to pay separately for breakfast, then you are fair game.

Three: there is nothing more terrifying than working in a room service kitchen in the morning when the orders keep streaming in faster than the chefs can cope.

So hotels charge needlessly large amounts for room service breakfast. Basically, they don’t want you to order it. And they will rip you off on à la carte breakfasts at the restaurant for the same sort of reasons. (Just eat off the damn buffet!)

There is also, let’s be honest, an element of profiteering here. You can go out for lunch and dinner. But 90 per cent of guests eat breakfast in their hotels. This makes them easy marks.

So should hotel rates be set by the government? Of course not. We are not living in Soviet Russia. And besides, once you start with hotel rates, why not individual restaurants too? Why not cars? Why not phones? There is no telling where this will end.

Ultimately, the market must decide. If guests think restaurants or hotels are too expensive, they should not go back. It is as simple as that.

But equally, the recent outrage must have shocked the hotel industry into realising that a little sensitivity is needed. Guests understand your need for systems. We recognise why you don’t want us to order breakfast in our rooms.

But at the end of the day, you guys are in the hospitality business. Show a little hospitality. Demonstrate some sensitivity. Encourage your employees to use discretion.

The public mood is changing. And hotels should learn to listen.

From HT Brunch, August 25, 2019