North Indians are always surprised when I tell them this but there is no real chaat tradition in South India. We know that what we think of our chaat originated in UP and Bihar. Chaat wallahs from those states fanned out all over India, taking their local food with them.

Delhi-wallahs like to ascribe ancient history to their chaat but with the exception of channa bhatura, which may be Punjabi-influenced, almost all of it seems to come from UP and Bihar. Even Daulat Ki Chaat, Delhi’s claim to fame, is in direct descent from Nimish, Malaiyo and similar UP desserts. (Many, if not most, of the guys who still make it in old Delhi have UP origins or come to Delhi from UP every winter.)

Kolkata chaat is loved by Bengalis but hardly ever made by them. Talk to the city’s puchka wallahs and you will be surprised by the number who come from Bihar or thereabouts. One theory is that the original chaat wallahs were from UP but that migrant Biharis have now taken over the trade.

Nobody in Mumbai disputes that the city’s famous chaat came from UP. Go to say, Chowpatty Beach, and you will find that the majority of the chaat wallahs are UP Brahmins. Many are called Sharma and like to be addressed as bhaiyya.

Of course the chaat of UP and Bihar has metamorphosed in every city it has travelled to. In Mumbai, the UP chaat met the city’s Gujaratis and bhelpuri was born of that association.

Intriguingly, the city’s other great street food dishes have very little to do with UP chaat. Pav bhaji is all Gujarati (though the pav suggests that the inspiration may have been the pav-keema of the city’s Gujarati Muslim neighbourhoods). Vada pav is all Maharashtrian and only really took off in the 1970s after the Shiv Sena adopted it. The classic Bombay sandwich is, as far as I can tell, totally indigenous.

So, why didn’t chaat spread south of Mumbai? Honestly, I don’t know. You do get chaat in South Indian cities now but it is always treated as an import – like say, tandoori chicken – rather than something that developed locally. By now, there should have been a distinctively South Indian version of the golgappa, but no, there really is nothing.

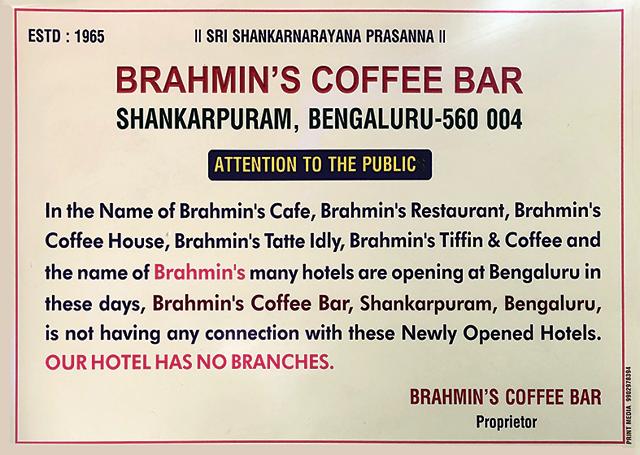

I went to Bengaluru last week looking for street food. I had great dosas, idlis and vadas at such local favourities as KTR, Veena Stores, Brahmin’s Coffee Bar, etc. (I was assured by trendy locals that MTR, my old favourite, is now passé) but as wonderful as the food was, it did not really qualify as street food. It was traditional food made in restaurant kitchens the classic way.

On the other hand, Bengaluru is full of street stalls. I deal regularly with the National Association of Street Vendors of India (who organise the phenomenally successful street food fairs in Delhi every winter, for example) and though the Association looks after the interests of all street vendors, food is one of its most high-profile activities.

My friend at the National Association, Sangeeta Singh, put me in touch with Mr. Rangaswamy, who runs the Karnataka wing.

Much of what Mr. Rangaswamy told me was not surprising. We make a lot of noise about our street food tradition, but in most Indian cities, ‘street food vendor’ is not a desirable profession. People who have a talent for food try and set up permanent eateries, no matter how humble, to give themselves the legitimacy and stability that comes from running a business.

But the guy who pushes a cart on the road or sets up a stall near a street lamp does it only because he has no choice. There are no jobs in the organised sector for him. He does not make pakoras on the footpath because he is a symbol of a new India. He makes them because he needs to find a way to feed his family.

Mr. Rangaswamy’s association has 25,000 members in Bengaluru, of whom around 5,000 are in the food business. Each of them tries to do something interesting or innovative, but life is hard. They pay hafta to the cops every day. They are pushed around by municipal officials. If it rains for a couple of days and they can’t open their stalls, then their families go hungry.

But despite the circumstances of their lives, all of them put their hearts and souls into their work and take genuine pride in making their customers happy.

Mr. Rangaswamy took me to a number of stalls where they made masala puri. This is a Bengaluru variation on what we would call in the rest of India. It’s channa with chutney, masalas and bits of papri (or puri shreds) for texture. It was nice enough but not sufficiently innovative (or so I thought) to qualify as a great Bengaluru chaat dish.

Next, we went to pav bhaji stalls. They had mountains of golden, yellow butter and hot tawas and their pav bhaji was tasty but not really indigenous to the region. Then, we went to the ‘Chinese thelas’. “They make egg rice,” Mr. Rangaswamy said, enthusiastically.

And indeed they did. But they made a lot more. And they made it well.

One guy had better wok skills than half the chefs I have seen cooking at Indian Chinese restaurants. He made a perfect mirchified mushroom fried rice in a minute, but was prouder of his own specialty: tawa pulao.

This turned out to be very strongly spiced fried rice with onions, pepper, ginger and an unmistakable Indian spice masala. I asked him if it was what I thought it was. It was, of course, pav bhaji masala.

Nearly everywhere I went in Bengaluru, two things struck me. The first was that pav bhaji masala turned up again and again as a basic flavouring in street cooking. The second was that at every single puchka place I went to, the pani for the puchkas was hot. Yet, hot; not a little warm. I have never seen this anywhere else in India.

It is a truth, not acknowledged often enough, that while North Indians think of the South in terms of vadas and dosas, the real national dish of South India is gobi manchurian. I wrote here, a year ago, about being horrified at biryani places in the old town of Hyderabad, which pushed manchurian over pulao. The same was true of Bengaluru. Not only do restaurants serve gobi (or kobi) manchurian and not only is it a staple of wedding feasts, but street vendors vied with each other to serve the best gobi manchurian. (Sorry. Not a fan.)

Overall, the food was not bad and though all of the vendors I spoke to were from South India, there was something about their tapori Hindi that made me curious. Where had they learned these dishes, I asked?

Mumbai.

They had all worked in Mumbai. Some had worked in Kamathipura, some in Mulund, some in Goregaon. But almost without exception, the more adventurous ones had all learned their craft on the Mumbai streets. Everything was Mumbai style, from wok skills to their dependence on pav bhaji masala.

Mr. Rangaswamy took me to a 99 Variety Dosa stall, one of many in the city, where dosas are made with 99 different fillings, ranging from Amul Cheese to paneer to cabbage to luridly-coloured sauces.

I spoke to the guy who made the dosas. I had two questions for him. One: was that distinctive spicy taste in his fillings pav bhaji masala?

It was.

Two: had he worked in Mumbai?

He had.

I don’t know enough about the subject to make generalisations. But I have a theory. Just as Lucknow became the centre of street food in the 20th century with UP vendors taking chaat all over India, so Mumbai is becoming a new centre for a new kind of chaat boom.

From the pav masala to the processed cheese to the wok-cooking style, every innovation seemed to have come from Mumbai, the city where manchurian was invented.

The street vendors I spoke to had left Mumbai, they said, because they couldn’t find space for their stalls. They had come back to introduce these flavours to their hometowns. They led tenuous existences but at least they were offering the people of Bengaluru new and exciting dishes.

It was an interesting thought. In the North we complain about how much chaat masala cooks pile on to everything.

But watch out! Pav bhaji masala is the chaat masala of the 21st century!

From HT Brunch, May 26, 2019