The rivalry between Lucknow and Hyderabad is one of the most intense cuisine-dramas in Indian history. I’ve lost count of the number of times I have heard the old verbal duels: who makes the better biryani; why is a Lucknavi dal so boring compared to its Hyderbadi competitor; isn’t a shikampuri a much greater kabab than the galouti; and on and on we go.

In actual fact, neither city should be able to lay claim to the culinary legacy of the Mughal empire. That distinction should go to Delhi, capital of the empire. But whatever the Mughals ate in Delhi during their golden age has been forgotten. There are people who will claim that a Delhi biryani is the best but usually, they are laughed out of the room before they can go much further.

Lucknow, home to the Nawabs of Oudh (or Avadh) became the centre of North Indian cuisine. Most of the great dishes of North Indian cuisine were invented there.

In contrast, Hyderabad was only a far-flung outpost of the Mughal empire. The Mughals despatched a governor to run the Deccan for them and called him the Nizam-ul-Mulk. When the Mughal empire crumbled, the Nizam became the ruler of that part of the Deccan (which included parts of today’s Maharashtra) and set up his own court.

The last great Nizam of Hyderabad was so rich and so mean that he made J Paul Getty look like Santa Claus in comparison. When the British left in 1947, the Nizam tried to join up with Pakistan to the horror of most of his subjects. The Indian government intervened, the old Hyderabad state remained a part of India (it is now scattered across, Andhra, Telangana and Maharashtra) and the Nizam retreated into a life of miserliness. His successor emigrated to Australia and over the years, the Hyderabad aristocracy declined. Now, it is hard to find nawabs or nobles who can still cook the food that was served in the Nizam’s court.

How Hyderabadi cuisine developed is still a matter of some dispute. I went to the new ITC Kohenur where I met up with Javed Akbar, an expert on Hyderbadi cuisine. Javed shot an episode of my old TLC show (Asian Diary) with me in Hyderabad a decade ago and throughout the shoot, he advanced two claims, both of which I thought were highly contentious.

The first was just eyeball-rollingly silly. Each time we were confronted by some greasy gravy or a cauldron of rice drenched in animal fat, Javed would intone solemnly, “In the old Hyderabad, this was regarded as a great aphrodisiac.”

Javed’s second claim was a little more credible. For much of the 19th Century and the early part of the 20th Century, the Nizam was the most important Muslim monarch in the world. The Ottoman empire had crumbled and the Arabs were simple Bedouins who had still to find oil.

The Nizam’s pre-eminence gave the Hyderabad court an exalted status and aristocratic families from all over West and Central Asia longed to become part of the Nizam’s world. So Hyderabad was closely connected to Morocco, Turkey, Egypt and many other Middle Eastern/West Asian countries. Many nobles from these nations gave their daughters in marriage to Hyderabadi nawabs.

So the cuisine that developed was different from Lucknow’s because it was enriched and refreshed by foreign influences, Javed argued.

Javed hosted a dinner for me at the new Dum Pukht Begums at the Kohenur getting the master chefs to cook dishes to recipes that had nearly been lost since the decline of the Nizam’s Court.

The food sounded Hyderabadi – Shikampuri Kabab, Dum Ka Murgh, Osmania Lagan ki Boti, Badami kheer etc. ---- but its distinctive feature was how subtle the seasonings were. The spice levels were low, there were lots of dry fruits and it was not hard to imagine that some of the flavours came from Persia or Turkey.

Javed’s mission is to secure the heritage of a vanishing Nizami Hyderabadi and the food (some of which will go on the Dum Pukht Begums menu when the restaurant opens officially next month) was fascinating.

But it wasn’t --- at least to my Philistine palate --- the sort of cuisine that epitomized the flavours of Hyderabad or even, showed them off to best advantage.

The point of Hyderabadi food is that when the cuisine of the Mughals met the flavours of the Deccan, something new and wonderful was created. The Mughals didn’t really understand spices (they were in short supply in Samarkand so they were not part of their heritage). Nor were they familiar with the sour flavours of South India (what we call Khattaash). The greatness of Hyderabadi cuisine derives less from culinary intercourse with Morocco and more from cohabition with the good people of today’s Telangana.

For my second fancy Hyderabadi meal at the ITC Kohenur we got Kulsum Begum (who had also featured in that old TLC series) to cook her specialties. Kulsum Begum is from an old Hyderabadi family and has access to traditional recipes but her’s is a living cuisine --- the sort of food that well-heeled Hyderabadis eat even today.

The dinner was spectacular. There was Gosht Ki Chutney: mutton cut into shreds and cooked with imli; Boti: diced mutton cooked with ginger, garlic red chilli; a Baingan salan with a peanut and imli gravy; Tursh Jhinga, griddled prawns with a sour marinade and a perfect kachcha biryani.

Like Javed, Kulsum has had a long association with ITC but her food represents a different kind of Hyderabadi cuisine. Its foundations may have been the Mughal dishes of old but while Lucknow’s chefs refined the cuisine through the use of aromatics and cooking techniques, Hyderabad took the Mughal basics and transformed the dishes with new wonderfully robust flavours.

The biryani was just one example. In Lucknow, the biryani (or pulao, as they call it) will be subtle and fragrant. Each grain will look like nothing much. But when you put it in your mouth, it will (if it’s done right) burst with flavour. In Hyderabad, they don’t waste much time on fragrance; they add spices and sourness instead.

Most north Indian biryanis are assemblies. You cook the meat and the rice separately. Then, you put them together in a pot, cook them gently and hope that the steam will marry the flavours. (Many chefs add a little concentrated stock to the rice to flavour it.)

In Hyderabad, they do make a biryani this way. But their real claim to fame is the kachcha biryani in which raw meat and rice are cooked together. As the meat cooks, it imparts its flavour to the rice.

A decade ago, when I shot in Hyderabad, we went from one celebrated biryani place to another looking for a great kachcha biryani. We never found it. Most restaurants made assembled biryanis which, even at the famous places, ranged from ‘over-rated’ to ‘rubbish’.

I decided then that perhaps, like most royal cities, Hyderabad had two cuisines. One was a haute cuisine, served at the Court which was expensive and required legions of cooks to make it.

But there was also a Cuisine Bourgeoise, comprising food that ordinary people made, which took elements of court cuisine and democratized them.

The last time I had come looking for this cuisine, I had gone away disappointed; nothing was really exceptional. But I resolved to look again.

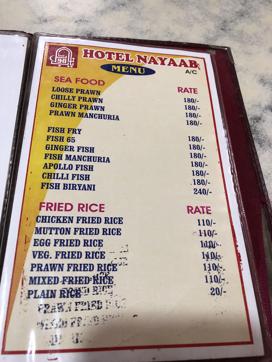

The first place I tried was Hotel Nayaab in the Charminar area, which looked grungy enough to be authentic. I tried the paya curry, the magaz fry and a masala mutton. Some of it was good but it bore little resemblance to the court cuisine that Javed and Kulsum preferred.

At Shadab, one of the city’s most famous restaurants, I had the legendary biryani (good), the Kababs (not so good) and something called Pakistan Curry (very good). At Chicha’s which was more upmarket than the grungy places and therefore should have been less authentic, I had the unexpected pleasure of discovering an excellent biryani and a wonderful tala ghost. At the famous Shah Ghouse Hotel, the biryani was outstanding but the rest of the food was not much better than elsewhere.

None of this was unusual --- not every restaurant can live up to the hype. But what intrigued me was this: even at small restaurants and dhabhas, there was no attempt to restrict the menu to Hydrabadi food. Nearly every single place served Butter Chicken. All (except perhaps for one) had tandoors and instead of the Hyderabadi kababs of legend, offered a Punjabi tandoori menu.

Most interesting was this: if you were to judge by local menus, then the greatest dish in Hyderabad is Chicken Manchurian. Every single restaurant had a list of Chinese dishes , even the dhabha-like Nayaab. At Shadab, there were huge queues for tables but when I wandered around the restaurant I was intrigued to note how many of the guests were eating Chinese food.

I counted eight different kinds of Chow Mein on the Shadab menu along with three kinds of Chop Suey. Even Shah Ghouse, legendary home of Hyderbadi biryani, offered Shanghai Chicken, Schezwan Chicken, and Lemon Chicken along with eight different kinds of Chinese noodles.

What does all this prove?

Well, it demonstrates that for those of us who are not lucky enough to be invited to private homes, the cuisine of the Nizams is hard to find. It was almost impossible to find a Kachcha biryani at most restaurants and the distinctive flavours of Hyderbadi food were melting into a pan-Indian mish-mash on the streets.

On restaurant menus at least, Hyderabad had lost out to Manchuria.

So do go to Hyderabad and eat your heart out. But remember that you will have to look very hard for the real thing.

This is one of two columns on Hyderabadi food. The companion piece will appear in Rude Food in this Sunday’s Brunch and of course, on this site.